Articles

Population turnaround

Could wage hikes lead to a minor baby boom in Japan? Possibly, according to research by the cabinet office – but let’s not get too optimistic, says TMAM portfolio manager Tetsushi Wakayama.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has been particularly vocal of late on the subject of tackling Japan’s low birth rate. It’s now or never, he urged in a January speech, pledging to double spending on a “child-first social economy”, spearheaded by a new Children and Families Agency. Concrete policy and funding details are expected to be outlined in June, but with a rising cost of living pushing some companies to talk about raising starting salaries, one hope is that wage hikes could help the country not only to escape decades of deflation – see our deep dive on Japan’s labour market from March 2023 for more details – but also to put the brakes on population decline.

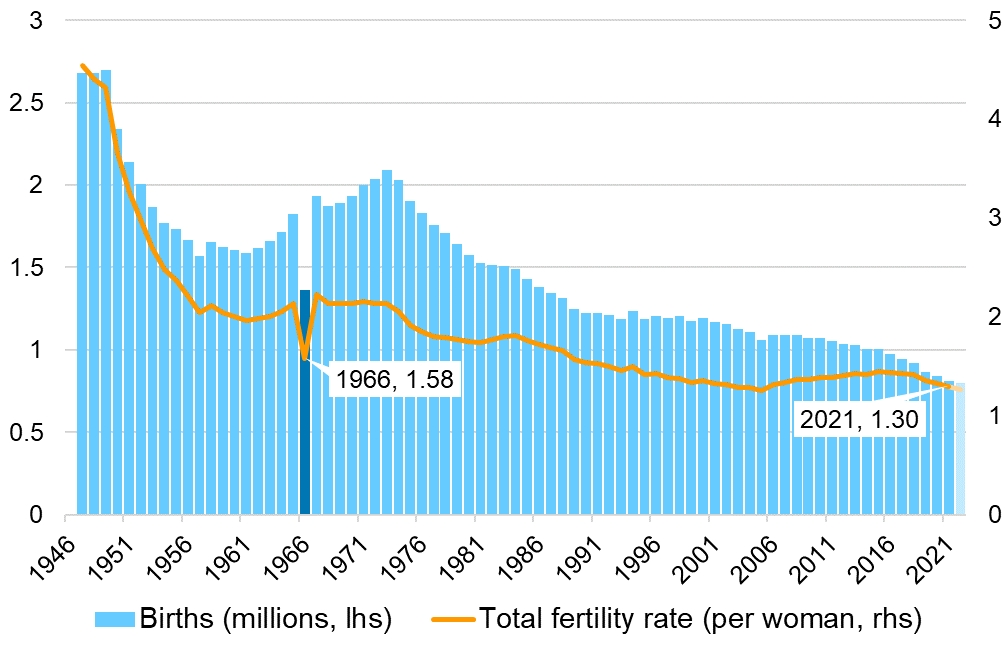

While demographic changes do not happen overnight, a recent cabinet office study extrapolates the link between marriages and births, and the marital status of men by annual income, estimating that sustained across-the-board wage hikes of 2% will increase the total fertility rate from 1.3 births per woman in 2021 to 1.4 a decade later. A shift away from seniority-based pay to more merit-based compensation could potentially see this figure rise above 1.5 as the same wage pot is distributed more heavily in favour of younger generations. Fertility itself is only one part of the equation, however, as the number of women of childbearing age continues to fall in absolute terms.

Increasing the birth rate may not be a silver bullet anyway: a recent UN study says greater gender parity in the labour force would do more to sustain economies in ageing, low-fertility societies than setting targets for women to have more children. Challenges facing Japan in this arena will include tackling a social insurance loophole that incentivises many married women to work part-time and stay below a certain income ceiling, and increasing parental leave uptake among men – up from 1.4% in 2010 to 12.7% in 2020, but still far short of the official target of 50% by 2025. Ahead of policy detail announcements next month is a moment pregnant with possibility; Kishida will need to convince a sceptical public that his government can deliver.

Sidebar: 1966 and the curse of the fire-horse

Japanese superstition has it that girls born in the year of the fire-horse – the 43rd year of a 60-year cycle – will grow up to kill their husbands. Such was the strength of this belief that in 1966, the fertility rate dropped 25% from the year before, with the impact especially prevalent in rural areas where parents worried about the future marriage prospects of a possible daughter born with this stigma. Urbanisation, sex detection in pregnancy and more modern attitudes in general suggest this pattern is unlikely to be repeated in 2026.

About the author

|

Tetsushi Wakayama, Japanese Equity Portfolio Manager

TMAM all-rounder, serving as economist, strategist and global equities analyst before moving to Japanese equities in 2020, first as investment research analyst covering banking, financials, and consumer electronics, and now as a member of the firm’s flagship GARP strategy portfolio management team. Tetsushi is also a long-suffering but optimistic supporter of the Chunichi Dragons baseball team. |

Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is intended solely for the purposes of information only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation by anyone in any jurisdiction in which such an offer or solicitation is not authorized or to any person to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation. This report has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.