Articles

Executive summary

- In a surprise move, the Bank of Japan raised the range for the 10-year JGB rate to 0.5%, explaining that the aim is to address the distorted yield curve and improve market functioning

- Governor Kuroda restated that he has no intention of hiking rates under current circumstances, and the existing scheme will be maintained for now with a slightly elevated yield curve

- The move may, however, be considered an indication of the beginning of the end of the ultra-loose monetary policy era

- Uncertainty over the possible timeframe of BoJ normalisation will impact equity markets in terms of valuations, as well as corporate profits amid currency fluctuations

Background to low wage growth: post-bubble gloom and demographic doom

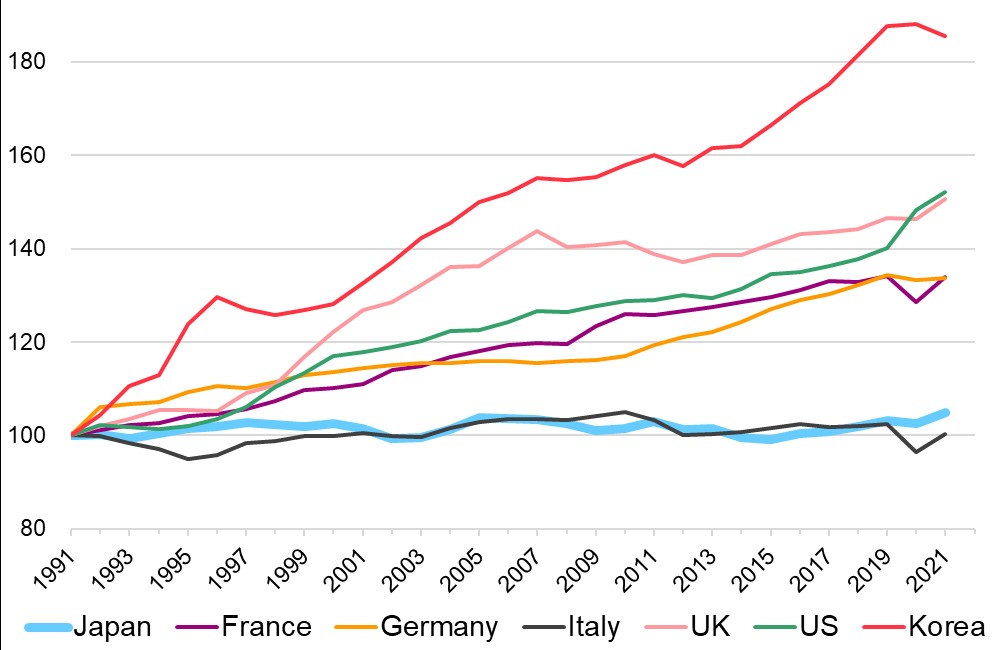

In the lost decades since Japan’s economic bubble burst, wage growth – in tandem with broader economic growth in the country – has been very slow. Productivity improvements have pushed up pay packets, but to a much smaller extent than elsewhere globally; and with labour productivity approaching a plateau, companies have shifted towards part-time and temporary workers to reign in rising fixed personnel costs. In addition, the impact of deteriorating terms of trade on both export and import prices has consistently lowered real wages, offsetting increases attributable to labour productivity growth. Japanese firms have sought to maintain profitability in a deflationary environment by curbing wages and other costs, rather than marking up prices as in the US, while employers and employees alike have chosen job security over profits and avoided lay-offs by limiting pay hikes, especially in hard times such as the post-bubble upheaval of the late 90s and the aftermath of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy.

Another reason for low wage growth can be found in structural changes on the supply side of Japan’s labour market. While the working-age population – defined as those aged 15-64 – peaked in the mid-90s, the actual working population has not decreased over the last three decades, with an increase in workforce participation by women and over-55s.

Abenomics in the 2010s helped create a more favourable environment for women in the workplace, with a sharp increase in the labour participation rate to over 70% making Japan a leader among G7 nations; the country’s ageing population, meanwhile, has pushed the proportion of older workers to 32%. The catch is that these two demographics tend to be in part-time employment, working fewer hours on lower rates than their full-time colleagues, and often in relatively low-wage service sector roles; this has resulted in lower average pay both per capita and per hour.

Structural changes and shifting paradigms

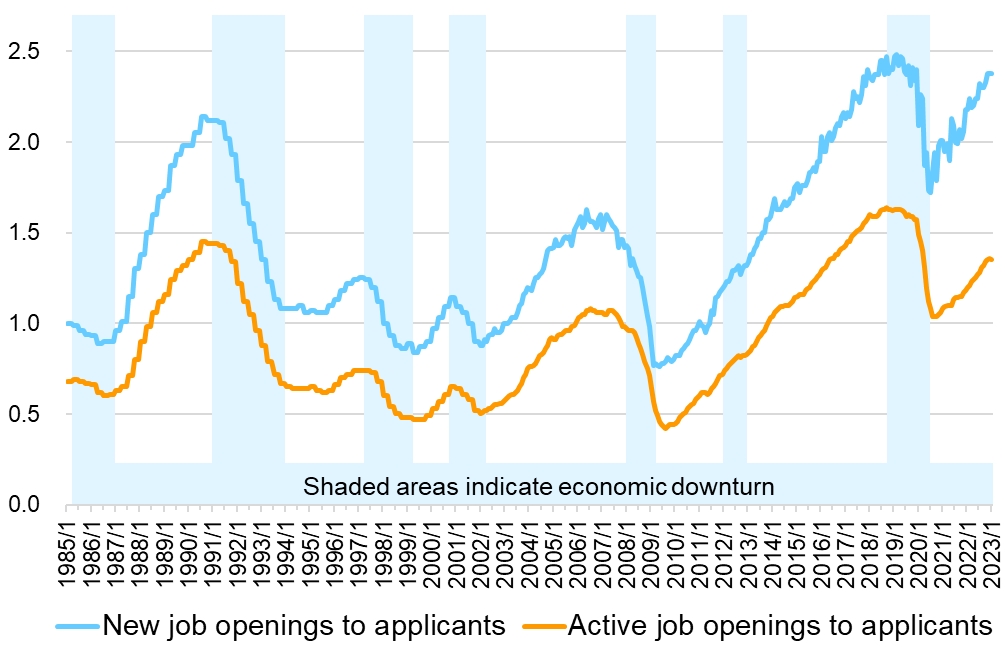

Recent years have, however, brought changes in the labour market. Participation in the workforce by women and retirees has reached mature levels; the labour supply is further limited by recent work-life balance legislation restricting hours for full-time workers, while tax benefits incentivise part-timers to cap their incomes. The proportion of part-time workers is no longer rising, and the wage gap between full-timers and part-timers is narrowing. With post-pandemic economic reopening increasing demand for labour, Japan is facing a structural shortage. Further tightness has come from Japanese companies – after decades of shifting operations overseas in a quest to lower pay costs –waking up to relatively low domestic wage levels, amid a growing need for highly skilled labour to produce competitive, high value-added products. The result has been job opening-to-applicant ratios rising to bubble-era highs, notwithstanding a temporary dip during the pandemic.

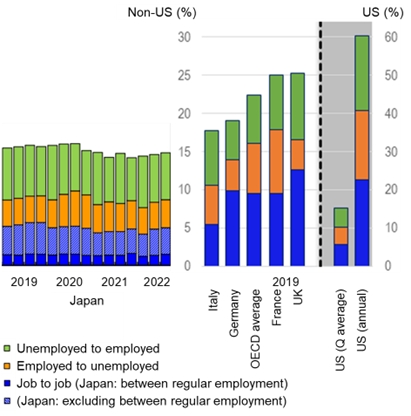

Another trend has been the shift away from the traditional lifetime employment paradigm to greater job mobility, an area where Japan has severely lagged other countries. This low mobility and consequent stagnation in career development has led to a lack of wage differentiation and a gap relative to international peers. For example, data analytics workers in the US receive 9% higher remuneration than the average for all jobs, versus only 1% more in Japan; US salaries in the field are 64% higher in absolute terms . Research indicates that countries with better job mobility show higher lifetime wage growth rates, as well as a greater appetite to develop skills . Covid-19 brought a dip in Japan’s mobility trend as companies acted flexibly to avoid staff layoffs – ANA, for example, temporarily seconded cabin attendants to local governments and high-end supermarkets – unlike in the US and Europe, where shutdowns and layoffs led to significant reshuffling; 2022 saw the trend start to recover, however, and there has been a spike in recruitment agency advertising encouraging younger workers to explore their career options.

Remuneration has already started to climb in segments where job mobility is relatively high, such as demand-sensitive in-person services, and among smaller companies and younger workers. We should watch whether this trend spreads to historically less mobile segments.

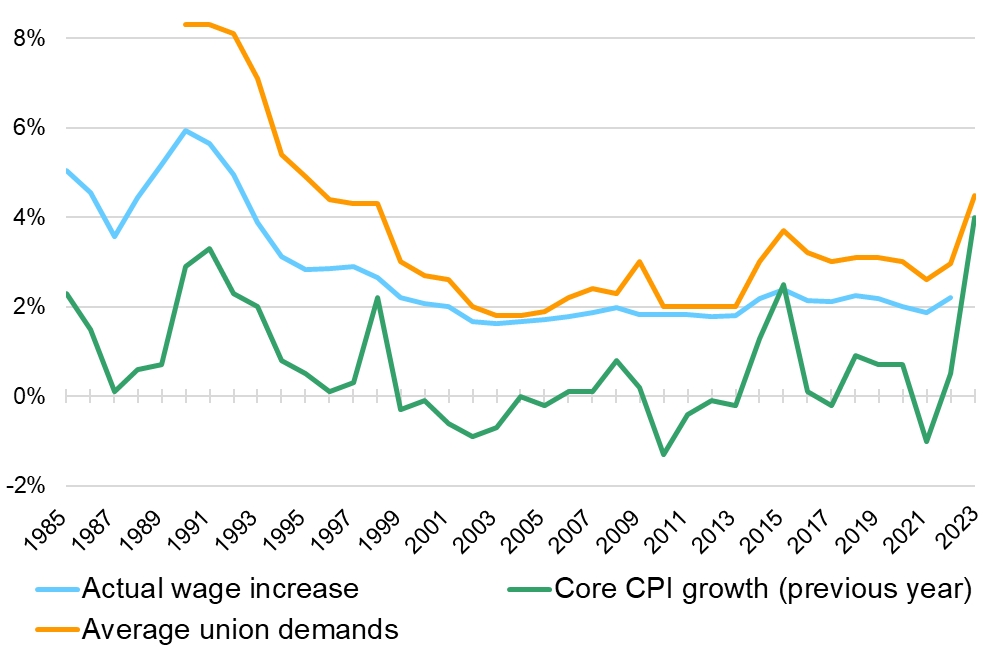

2023 pay talks signal new narrative

Spring in Japan is the season for shunto, the annual wage negotiations between company management and unions, and this year some firms have already announced significant wage hikes in response to a tightening labour market and rising inflation. Given 2022 CPI growth of 4%, expectations are for remuneration to increase by over 3%, which would be the highest since 1997. Even the conservative-leaning Keidanren association of business leaders has broken from its usual stance of curbing wage increases to control costs, telling its members in January that “management has a duty to increase wages to keep pace with rising prices”. The expected 3+% figure includes seniority-related pay increases of around 1.8%, meaning a pure wage hike of around 1 to 1.5%, which is still low compared to the rising cost of living; the underlying message, however, is that inflation and labour supply shortages are being seen as major factors in deciding pay, with wage hikes becoming the norm. Forecasts suggest similar increases in 2024 even after inflation slows; this will be another trend to watch.

Market and monetary policy implications

With wage bills and other input costs rising, companies will need to either improve productivity or raise prices (ideally both) if they are to avoid a fall in profits. Firms announcing significant wage hikes have so far received a largely positive market response, based on solid fundamentals outweighing any negative direct impact on margins. Winners going forwards will be those firms that can pay higher wages to secure and retain quality talent, allowing them to successfully raise prices, and reap the benefits in both corporate and share performance.

The Bank of Japan is looking for a virtuous cycle of sustained inflation and wage growth, allowing it to move from the current ultra-easy monetary policy towards normalisation. The spring pay talks and broader wage movements are, in this sense, of great interest to capital markets, as BoJ governor-in-waiting Kazuo Ueda has commented that his actions will be based on the observed economic and price situation. The central bank views sustained wage growth of 3% as ideal, with 1% coming from improved labour productivity on top of a longstanding 2% CPI target; this will take some time to achieve, but concrete signs would be a catalyst to start normalising monetary policy.

Japan’s economy is coming to a turning point, where growing acceptance of inflation caused by higher input prices can be parlayed into a secular inflationary environment with wage growth, under demographic tightening in the labour market and a post pandemic demand recovery. Emerging structural changes in the country’s labour market including higher mobility, greater investment in human capital, and a shift away from the loyalty-focused lifetime employment model to a more career-oriented mentality pave the way to productivity gains, which will be needed to maintain current wage growth momentum. Change in Japan is rarely fast, but with corporates already moving ahead and government pressing in the same direction, Japan Inc. looks ready at last to make real progress.

Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is intended solely for the purposes of information only and is not intended as an offer or solicitation by anyone in any jurisdiction in which such an offer or solicitation is not authorized or to any person to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation. This report has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore.